Don't miss any stories → Follow Tennis View

FollowApproach With A Plan

Traditional Approach

From a stroke mechanics standpoint, traditional approach shots involve the same core elements as primary groundstrokes (see chapter 4). But because successful primary approach shots are struck from well inside the court (figure 8.1), adaptations such as compacting the backswing or flattening out a swing path are often necessary. These quick modifications are based on the ball’s incoming speed, spin, trajectory, and landing zone, as well as the approximate strike zone (in relation to the body).

In terms of targets for the approach shot, depth is king. A deep approach provides valuable time for the player to establish an offensive position at the net while forcing opponents to defend from behind the baseline. This positioning often causes opponents to lean back and open their shoulders. In turn, the angle of the racket face soon follows. This overrotation causes the passing shot to float well above the net, yielding a comfortable, high volley. Players have three primary options when hitting a deep approach shot.

Deep to the Backhand

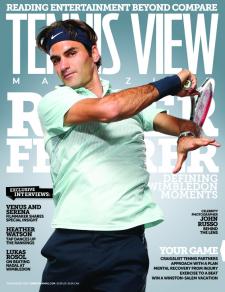

When a player is picking which side of the court to direct the approach shot toward, a simple lesson in anatomy offers some useful revelations. An opponent who is coiling to hit an offensive passing shot off the forehand wing has the luxury of having the dominant hitting shoulder behind the body. This means he can hit the passing shot three feet later and still strike an offensive blow. The same player coiling to strike a backhand pass has the dominant hitting shoulder in front of the body. This means that if contact is late, he only has two options: (1) to attempt a defensive slice backhand or (2) to spend the required hours educating and coordinating his nondominant hand to hit a two-hander. This is why hitting the approach deep to the backhand is a good tactic versus opponents who use a one-handed backhand. For a successful passing shot, a one-handed topspin backhand, such as Roger Federer’s, is actually struck a foot in front of the front hip. This early contact prevents a one-hander from “holding the pass,” or making contact toward the back of the strike zone (as a two-handed player like Rafa Nadal tends to do). When late, a one-hander has to abort the offensive topspin passing shot and revert to the open-face chip reply. This higher, slower return often results in an easy volley put-away. This strike zone issue is the reason why the one-handed backhand is now on tennis’ endangered species list; it simply lacks the disguise and options that are available when players use a fully developed two-handed backhand stroke. The decision on whether to attack an opponent’s two-handed backhand wing depends greatly on its quality and how the opponent executes it under pressure compared to the opponent’s forehand. If an opponent’s backhand is her weaker shot, the deep approach shot to the backhand may still be the best option.

Deep Down the Middle

More net-rushers would be wise to take advantage of this law: Angle creates angle. When players are pushed wide, more severe down-the-line and crosscourt passing angles become available. However, attempting a passing shot off a well-struck deep approach shot down the middle is a daunting task. From the opponent’s perspective, creating an angle is much more difficult. This will be the go-to approach tactic on the ATP tour in the very near future. The heights of men’s professional tennis players are soon to reach the 7-foot (213 cm) mark. The next generation of incredible athletes will have the wingspan of a 747. That extended reach combined with an approach shot deep down the middle will be a million-dollar tactic.

Deep to the Forehand

With the dominance of the two-handed backhand, this shot has frequently become a player’s more dependable shot. The use of both arms gives the two-handed backhand stroke a consistently quieter racket face through the strike zone, and the arm–body rotation is synchronized cleaner than on the forehand side. So, at the higher levels of the game, hitting the approach deep to the opponent’s forehand is often an effective strategy.

Here’s another interesting insight to consider: Players often have a formidable offensive forehand groundstroke but a severely underdeveloped defensive forehand. The same player may have a backhand with an average offensive component but may be world class when pushed into a defensive or neutralizing backhand. So, when the player is on defense, where’s the weakness? Players shouldn’t be afraid to attack the forehand just because it’s a forehand.

COACH’S CORNER

Besides the approach shot, hitting groundstrokes deep down the middle is also a useful tactic. Here’s a quick story that illustrates the effectiveness of this tactic. Before the 2011 Sony Ericsson WTA finals in Miami, I was talking with my good friend Sam Sumyk. Sam is one of the top coaches in the world and currently coaches Victoria Azarenka. Vika was set to play Maria Sharapova in the finals the next day.

Sharapova is a formidable opponent, and I’m a big fan of her work ethic, perseverance, and commitment. The strategy was to have Vika focus her attack deep down the middle, thus making Maria get out of the way of her own strokes—arguably her least effective footwork pattern—and try to create winning angles where there were no angles to create. Minimizing an aggressive player’s angles can pay off bigtime. Maria made eight unforced errors in the first game alone as Vika went on to take the title 6-1, 6-4.

*Excerpt from Championship Tennis, ISBN978-1-4504-2453-0, published by Human Kinetics

This article is from the July/Aug 2013 issue |

|

|

SOLD OUT Subscribe now and you'll never miss an issue!

|