Don't miss any stories → Follow Tennis View

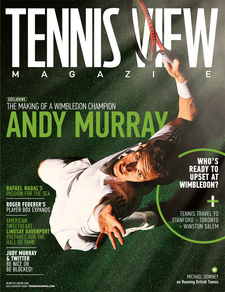

FollowAndy Murray - The Making of a Champion

Exclusive Interview with Andy Murray

There’s an almost ethereal hush around Wimbledon in the days leading up to The Championships. The gentle yet eerie quiet is punctuated only by the murmurs of coaches, the occasional burst from the public address system and the soft thwack of racquet on ball around the back courts of the All England Club.

For Andy Murray, it’s a rare chance to collect his thoughts and absorb the unique atmosphere before the inevitable annual hysteria begins to unfold once more. This will be Murray’s ninth visit to SW19 as a professional, but 12 years ago, his Wimbledon story began in very different circumstances.

Back then, Murray was far from the 185-pound, physical specimen he is these days. As a 15-year-old wildcard dwarfed by some of his competitors, few onlookers would have even noticed as he lost in three sets in the first round of the junior tournament. In 2002, Tim Henman was the darling of the crowds, but Murray’s potential as a future successor was already well known to those involved in British tennis. At the age of 12, the young Scot burst onto the radar by winning the prestigious Orange Bowl title, defeating players almost two years his senior

Murray was determined to live his dream of competing with the very best in the Grand Slams, but the thought of a tennis career was vague.

“I knew for a long time that I wanted to eventually turn pro, but it’s hard to say when I first realized it would be possible,” he told me recently. “Winning big tournaments like the Orange Bowl as a junior definitely fills you with confidence that maybe one day you can compete at the highest level. But a lot of players have won the Orange Bowl and then not gone on to become pros, so it was far from guaranteed. It wasn’t until I won the US Open junior title in 2004 that I really thought I could make it.”

Destined To Be A Winner

As a teenager, Murray’s considerable talents were initially nurtured by the affable Leon Smith, who currently serves as British Davis Cup captain. Their paths first crossed when Murray was playing tennis at the age of 7, but even then it was obvious he was a born winner.

As a teenager, Murray’s considerable talents were initially nurtured by the affable Leon Smith, who currently serves as British Davis Cup captain. Their paths first crossed when Murray was playing tennis at the age of 7, but even then it was obvious he was a born winner.

“The qualities that you see in Andy now are something he's probably had since birth,” Smith said. “He fights hard, he hates to lose and he’s always had that combination of competitiveness, professionalism and attention to detail.”

Growing up, Murray idolized Andre Agassi after watching enthralled as the pony-tailed showman from Las Vegas won Wimbledon in 1992. But while he shares Agassi’s bullet return, the similarities end there. When it came to his own game style, Murray has always been resolutely individualistic, only looking to other players when he felt it could benefit him. He spent one off-season studiously analyzing videos of Pete Sampras’s service motion in an attempt to gain some extra rotation and power.

“I wouldn’t say my style is modelled on anyone,” he said. “I work hard on every aspect of my game all the time, and I always have done. I haven’t ever consciously thought I want to hit the ball like a certain player. It's important to me to have my own unique style.”

Murray has never been afraid to do things his own way and make tough decisions for the good of his career. Shortly after that first Wimbledon appearance in 2002, he abandoned his childhood home and uprooted to Barcelona. He barely spoke a word of Spanish, but he had heard first hand of the array of practice partners and facilities on offer to Rafael Nadal in Mallorca, and he quickly realized that if he stayed at home, he risked being left behind.

Murray came under the wing of former world No. 7 Emilio Sanchez, who owned an academy on the outskirts of the city. Sanchez was about to discover the intense drive and focus that would quickly establish Murray as the star performer in his squad. As he recalls with a laugh, though, his first impressions were anything but positive.

“He came with very good reports saying he was very talented, but when I first met him, he was walking with his head down and shoulders slumped, and I was thinking, ‘He doesn’t look like much of a player!’”

Sanchez soon found that, with Murray, appearances can be deceptive.

“He’s always been extremely passionate, even if he doesn’t always show it,” he said. “It meant he put more effort in than players, he worked harder and he substituted the things which were maybe initially lacking in his game with that passion. That’s why he’s become one of the best in the world and won Grand Slams.”

Murray’s ferocious, almost obsessive work ethic has always been key in transforming perceived weaknesses into strengths. Sanchez was impressed by his intrinsic ability to anticipate and read his opponents’ every intention. While his movement is now held up as a shining example for other players, those quick changes of direction weren’t always so natural, especially for a teenager starting to undergo a growth spurt.

“What was immediately impressive was that he had a lot of resources to answer whatever you did to him,” Sanchez said. “He had good hands, and if the other player came to the net, he would always make him volley or pass him. When they attacked him, he would counter-attack even faster. But we had to work a lot on his footwork. With most of the players from Spain, there’s a difference in the way they move. It always seems like they have more time and more options of where to hit the ball. By the time he was 17, Andy began to move so well that whether he was defending or attacking, he was always balanced.”

Unafraid Of New Challenges

Murray was a quick learner, and with Sanchez, he began to learn the value of letting his opponent lose rather than always feeling the need to go for winners. And with practice partners like former world No. 1 Carlos Moya regularly dropping by, Murray was never short of a challenge.

“Andy was always a player with a lot of character,” Sanchez said. “One of his best qualities was that he was never afraid of anything. Moya was amazed as they were hitting and Andy was taking him on. Every time he faced a new challenge, he found a way to step up and showed he had the tools to cope. That’s down to mental toughness within the player as well as talent. Andy always believed and had very high expectations. His goals seemed very high and demanding, but he had a clear idea of how he wanted to get there, and throughout his career he’s found ways to break barriers to achieve them.”

Murray grew up regularly playing against adult players at his local club from the age of 5. He feels that playing them helped install that fearless mentality whenever he moved to the next level.

“From a very young age, I played a lot against players who were much older than me, which was great for my confidence back then,” he said. “When I moved up to the higher levels of competition, it was easier for me to compete and play my best tennis despite the age gap. It also gave me that innate confidence and self belief, so when I played, I believed I could win.”

The Power of Sibling Rivalry

Having an older brother, Jamie, who was for many years both bigger and stronger than Andy, also helped in his development. Their mother, Judy, is full of stories of how the two brothers would relentlessly taunt each other as kids if either came second-best at anything.

“Jamie and I were both very competitive when we were younger in pretty much everything we did,” Murray smiles. “Whether we were playing football, tennis or even racing around the garden, we always wanted to beat each other. It’s a trait we’ve both carried into our professional careers. I've also got a good record against lefties thanks to Jamie.”

Murray may only see his brother fleetingly on tour, when their busy schedules coincide, but he’s fiercely proud of his career as a doubles specialist, and they have teamed up on many occasions. They competed together in both the London and Beijing Olympics, as well as winning multiple tour-level titles. Murray strongly disagrees with John McEnroe’s suggestion that doubles doesn't appeal to fans and that the game should be eliminated.

“I wouldn’t agree it’s no longer relevant. It’s been an important part of the sport for a long time,” Murray counters. “Maybe there is room to improve the format so more people watch it, but I definitely don’t agree with scrapping it altogether. Doubles specialists like my brother can and do have very long and successful careers, and they also work extremely hard on and off the court.”

Growing up, the brothers dreamed of winning Wimbledon titles, and Andy's victory last summer meant that they had finally both achieved their childhood ambitions. Jamie may not quite have scaled the same heights, but his mixed-doubles victory with Jelena Jankovic in 2007 was the first title by a British player at Wimbledon in 20 years. However, it took a surprising length of time for them to get together to reflect on Murray’s history-making exploits.

“We managed it eventually,” he laughed. “Jamie had to fly out for a tournament the day before the Wimbledon final and then ended up going on quite a good run right up to the end of the season with his doubles partner John [Peers], so we didn’t actually get to fully catch up until Australia earlier this year. We are both really competitive, so there is always banter flying backwards and forwards. It's great that we’ve both managed to get our names on the wall at the All England Club, though!”

The nature of Murray’s character means that he’s far from satisfied with just one Wimbledon title. With several more years of his prime to come, his relentless appetite for progress continues.

“The key is to never stop working. You can always improve,” he said. “The game is pretty physical these days, and one of the main reasons I can play the way I play is because of my physical conditioning. But it’s also getting tougher. There are a lot of promising young players coming through, and there are also a lot of strong older guys on the tour. It’s probably the closest the tour has ever been in terms of competition. It’s gotten tougher for everyone to win tournaments, which is great for the fans.”

But as the queues begin to form and the countdown to the start of The Championships intensifies, one cannot help but wonder if Murray occasionally misses those simpler times at the start of his career, when expectations were lower and he could sneak through the famous gates almost unnoticed. Back then, tennis framed life rather than the other way around.

“Not really,” he says. “I travel a lot, which can be quite hard. It means I don’t get to see my family, my girlfriend or my dogs as much as I would like, but I definitely wouldn’t change anything. I’m incredibly fortunate to be able to do what I do as a job, and life has turned out pretty well so far!”

This article is from the July/August 2014 - Wimbledon issue |

|

|

SOLD OUT Subscribe now and you'll never miss an issue!

|